I think there are two types of business books ; those that are a slog, full of jargon and information that you would nearly need to put a pair of wellies on to trudge through, and those that are page turners, weaving information, research and data through a narrative style that is a delightful ease to read. The second type is also more memorable by the way, as research shows that if we combine our hard facts and data with the human skill of storytelling, the reader is multiple times more likely to engage with and retain the information relayed. (side note : if you’re interested in the power of storytelling as a strategic business tool, I deliver training on that.)

Amy Edmondson’s latest book ‘Right Kind of Wrong – why learning to fail helps us to thrive’, happily falls into the latter category. I was as absorbed by it as I would be by a Maggie O’Farrell novel. Aside from being an enjoyable read, the book is teeming with insights and useful knowledge. I read it with a pencil and post-its and was voraciously underlining and marking as I went.

I’m going to break the book’s learnings into 3 parts :

- The failure landscape

- The science of failing well

- Action : thriving as a fallible human being

Part 1 : the failure landscape

‘’The only man who never makes a mistake is the

man who does nothing’’

Roosevelt

Learning to fail

The failure landscape is all about learning to fail, and understanding why we human beings have such an aversion to it. Edmondson reminds us that we all fail. We will all continue to fail. But it’s not comfortable for us to fail, especially publicly in front of others, such as our work colleagues. But when we avoid failure, it is impossible to take the valuable learning opportunities available within it on board. Learning from failure takes emotional fortitude and skills.

‘’High performing individuals aren’t used to making mistakes. It’s important to learn to laugh at ourselves or we’ll err on the side of being too afraid to try’’. Jen Heemstra

Recognise the Fixed Mindset in the quote above? More on that later.

Psychological Safety

Unsurprisingly, given that it is Amy Edmondson who wrote the book, psychological safety features prominently.

‘’In my research I’ve amassed a fair amount of evidence that psychological safety is especially helpful in settings where teamwork, problem – solving or innovation are needed’’. Edmondson.

You can’t have problem – solving and innovation without failure, and you can’t have failure without an environment of psychological safety. What psychological safety enables in terms of failure is blameless reporting, the ability to speak up quickly and without penalty about errors.

A key insight from the book is that not all failures are equal.

The 3 failure types :

Basic

Complex

Intelligent

In a nutshell, they differ in terms of levels of uncertainty and preventability.

Basic failures can nearly always be averted. They occur in situations of very low uncertainty and high preventability. Such as reverse parking and hitting a lamppost. You’ve done it many times before and there were no unknowns. These kinds of errors are caused by : inattention, making assumptions, overconfidence, neglect.

Complex failures have more than one cause, and tend to occur in familiar settings. Beware a false sense of security and overconfidence here.

Intelligent failures are the ones we should be having more of! They are the right kind of wrong. We are out of our comfort zone with these, stretching and challenging ourselves, like a beginner on a yoga mat trying to enjoy downward dog.

Intelligent failures :

- Must take place in new territory

- In pursuit of a valued goal

- With adequate preparation and risk mitigation.

(side note : the ex- teacher in me was delighted with the amount of times Edmondson referred to the importance of doing your homework around intelligent goals!)

On Innovation and intelligent failure : ‘’innovation occurs in new territory where a compelling solution is yet to be developed’’. In other words, they go hand in hand, like cheese and wine. The right kind of wrong.

Edmondson expands in great depth, using real life situations and scenarios, on the three failure types, as well as including plenty of information on how to reduce and prevent basic and complex failures.

Failing well, she shares, ‘’requires us to become vigorously humble and curious, a state that does not come naturally to adults’’. Adulthood is so overrated, I think, not for the first time in my adult life.

We need to park the ego, preferably in a remote car park many miles away, and choose learning over knowing.

Part 2 : the science of failing well

She gives us 3 aspects to this : (aren’t things that come in 3s very satisfying?)

- Self awareness

- Situation awareness

- Systems awareness

Self awareness

Requires a mindset shift from :

I’m right – which is ego

To

How do I know I’m right? Which is humility and curiosity

‘’Failure is ego threatening which causes people to tune out’’.

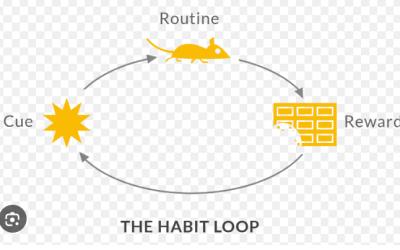

To become good at failing (not at all an oxymoron), we need to look at ourselves, particularly at our thinking styles, our attitude to learning over knowing, and the biases that reinforce our certainty and ego, notably confirmation bias and sunk cost fallacy.

But learning from failure is difficult. Failure threatens our self esteem, we don’t speak up about it, reinforcing the quiet power of shame. But making mistakes doesn’t mean we’re terrible. It means we are fallible human beings.

The key is to seek the learning.

To choose learning over knowing.

Because it’s very hard to learn if you already know.

Reframing.

‘’ the overarching skill that ties the self discipline of failing well together is framing – or more precisely, reframing’’.

Carol Dweck’s Growth Mindset vs Fixed Mindset is an example of a cognitive frame. If we have a fixed mindset about our intelligence, about our success, then it can be very hard to accept or admit to a failure. We are also less likely to stretch and challenge ourselves to take on the intelligent failures.

Other cognitive frames include : playing to win vs playing not to lose; learning orientation vs execution orientation.

Situation awareness

Is a question of context. ‘’Too many preventable failures occur because of insufficient attention to context’’.

2 dimensions of context :

How much is known (degree of novelty / uncertainty)

What’s at stake (risk)

The correlation is substantial between failure type and context type :

Intelligent failure – novel situation – eg science lab

Complex failure – variable situation – eg operating room

Basic failure – consistent situation – eg assembly line

New contexts and intelligent failures go hand in hand. And ‘’just as we spontaneously underestimate uncertainty, we overestimate what’s at stake’’.

Systems awareness

‘’Only by considering the relationship between the parts can you explain a system’s behaviour’’.

We often make decisions without considering the ripple effect of unintended consequences they may have. Practising systems thinking expands our lens from the ‘here and now’ to include the ‘elsewhere and later’.

Questions to ask to assess the consequences :

- Who and what else is affected by this?

- What might happen later, as a consequence of doing this now?

Examples of systems designed for Innovation excellence include : Google’s X and the Toyota Production System (TPS). Edmondson uses these examples to illustrate how system’s awareness is crucial to innovation, by welcoming intelligent failures.

‘’Mastering systems awareness starts with training yourself to look for the wholes, rather than zooming in, as we do, on the parts’’.

Part 3 : Action – Thriving as a fallible human being

This book, Right kind of Wrong, offers us a new way of thinking about failure, and a very useful framework with which to consider the failure landscape. What is required from us is the willingness to learn to think differently. This starts with accepting our fallibility. And with learning how to fail well – to minimise or prevent the basic and complex failures, and to cultivate an appetite for more intelligent failures.

One of my favourite stories in the book was that of Barbe Nicole Ponsardin Clicquot, the woman in the late 1800s who on the death of her husband defied all societal and market odds at the time to create one of the most successful champagne businesses of all time. She was a woman who’s failures were intelligent – they were in new territory, pursuing a valuable opportunity, and taking risks in a managed and calculated way.

To finish, Edmondson offers us some basic failures practises, to equip us with the tools to fail well as a fallible human being. They are :

- Persistence – anyone familiar with the work of Angela Duckworth on Grit will be familiar with this. Persistence is sustained effort over time, and is crucial to success. The creation story of Spanx is a good example.

- Reflection – ‘to reduce the preventable basic and complex failures in our lives, it’s crucial to invest time in deliberate and honest reflection’’. How will we ever take the learnings from the things that go well if we don’t reflect on them?

- Accountability – a beautiful strength lies in ‘I did do it’, rather than blaming.

- Saying your sorry – perhaps the hardest one of all for many of us! ‘’The role of an apology is to repair’’. Possibly my favourite line from the whole book.

Healthy failure cultures accept failure as a byproduct of innovation. The world is in a constant state of evolution, requiring continuous innovation on the part of us humans. Without failure there can be no innovation. But as Edmondson shows in her book, not all failures are equal, and there is a science to failing well.